In his latest opinion piece Allister Young, Chief Executive of Coastline Housing, takes a practical look at the rising homelessness crisis and talks about how we might begin to close the gap between hope and reality in the future.

Last Thursday had quite a big focus on homelessness for me. I spent the morning shadowing with colleagues in our Homeless Service team, and the afternoon chairing a meeting of the Cornwall Housing & Homelessness Alliance. So I had some time out and about with colleagues, talking with people actually experiencing homelessness, and some time with people talking about Cornwall’s overall strategy for dealing with homelessness. It was interesting to do both things on the same day, and to see the huge gap between where we (Cornwall, and the rest of the country) would like to be, and where we actually are. The gap between hope and reality.

I want to talk about how we might begin to close that gap between hope and reality, but there are two things I’d like to say first, because I think they’re important to understand before considering what the solutions might be.

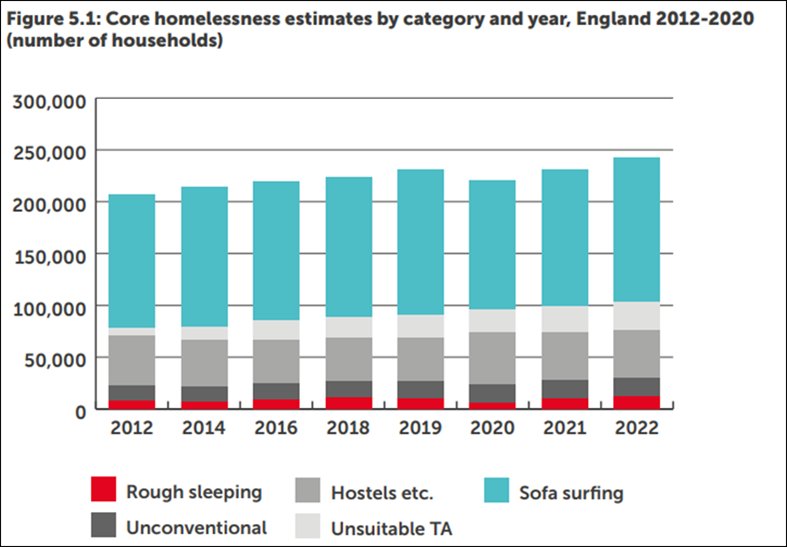

First of all, homeless isn’t just about people ‘sleeping rough’. That is the tip of the iceberg. The graph below is from Crisis’s 2023 homelessness monitoring report. It shows that there were nearly 250,000 people who were homeless in 2020, of which fewer than 5,000 were sleeping rough. The vast majority of people experiencing homelessness are mainly sofa-surfing or in some sort of unsuitable temporary accommodation.

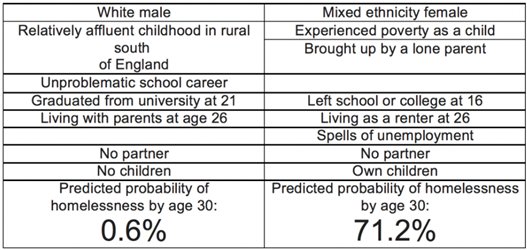

Secondly, people often say we’re all only one or two paycheques away from becoming homeless. While there is some truth to that, it hides a starker reality about who becomes homeless. Research from the London School of Economics shows that if you live in poverty when you are young, or if you come from a group that is more likely to be economically disadvantaged, or if you suffered from adverse childhood experiences, then you are much more likely to experience homelessness later in life.

Consider the two comparisons in the table below, showing how likely someone is to experience homelessness by the time they are 30, depending on their background. Then think about whether we all have the same chance of becoming homeless or not.

So, with those two things out of the way, understanding the size of the problem, and some of the things that might cause it, we can get a bit closer to talking about solutions.

I spoke at an event about homelessness and poverty hosted by Exeter University’s Institute of Cornish Studies in October this year. For my talk, I decided to look at homelessness through the lens of the law, and how the law decides if you are ‘entitled’ to support or not if you are homeless.

The starting point for the law is judging whether you have made yourself ‘intentionally homeless’. That got me thinking, are people really choosing to make themselves ‘intentionally homeless’, or is the choice being forced on them? My conclusion was that homelessness is a choice, but it’s a choice that has been made by successive governments through the policy decisions they have made (or not made), more than it is a choice made by the people who end up being homeless.

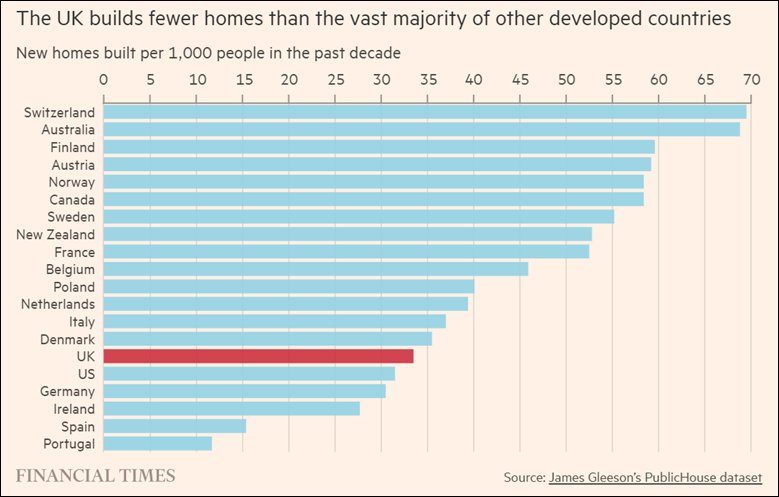

Consider the evidence of the chart below. We are pretty much the worst in the developed world at preventing homelessness. We might be relatively good at keeping the numbers of people rough sleeping down, but we have more people without a decent secure home than any other ‘developed’ country. Surely that means there are difference choices we could be making as a country?

So if there are different choices we could be making that would help provide solutions to the issue, what are they? Well, here are some ideas. You’ll be familiar with most of them from some of my previous opinion pieces.

First of all, we should build more homes, particularly social housing. It’s generally agreed that if everyone is to have a decent quality, safe, secure home, we need to be building around 300,000 homes a year. We’ve not managed that since the early 1970s. Other countries seem to be able to do it (including Belgium, which didn’t even have a government for about 1,000 days between 2010 and 2020…). Building homes isn’t the be all and end all of ending homelessness, but it’s a pretty important starting point.

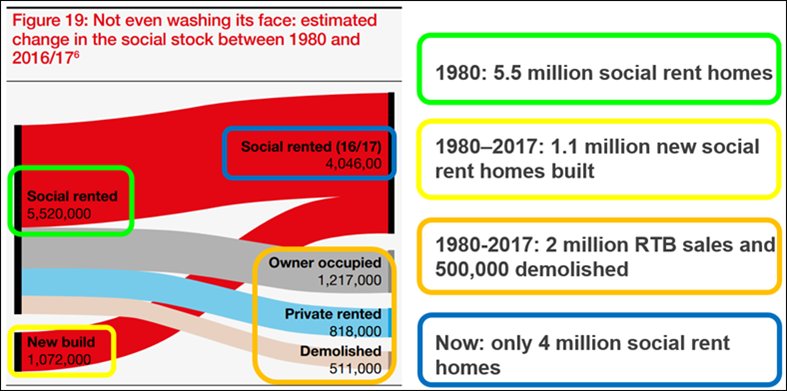

Secondly, we should scrap the Right to Buy, or at the very least stop selling the social homes at a discount. The Right to Buy might have had a role to play when it was introduced in 1980 when levels of home ownership were low, and we didn’t have such a stark housing crisis. It doesn’t have a role to play in any sensible housing or economic policy now.

As a result of the Right to Buy, two million social homes have been sold since 1980, nearly twice as many as have been built over the same period. And nearly half of the homes sold through the Right to Buy are now private rent, often being let to people who would have lived in them when they were social housing. Increasing the number of secure, affordable social homes for people to live in has an important part to play in ending homelessness.

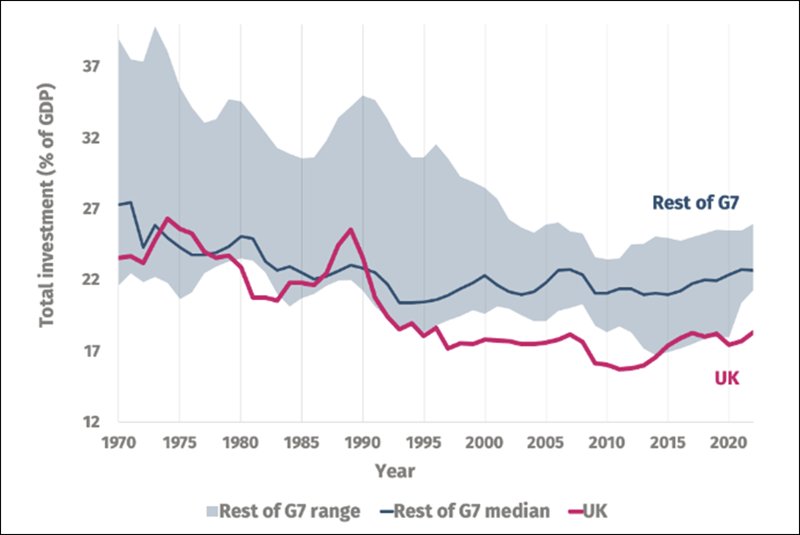

Thirdly, we should have a more proactive long-term approach to how we spend money. We always seem to focus on short term budget cutting, rather than investing in our future. The result is we invest a lot less in infrastructure, housing or crucial health and care services than other countries. It means people are more likely to end up in situations where they need emergency support, when we could be investing in solutions earlier, before things go wrong.

It’s the sort of thinking that results in the graph I shared previously – which showed that 40 years ago 95% of our spending on housing was on buildings, whereas now 90% of it is on benefits. Supporting people early, before they’ve hit rock bottom, is obviously better for them, and it’s also much cheaper in the long run.

I’ll finish by quoting Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick, the author of the LSE report I referred to earlier. She said: “Homelessness is miserable, unfair, and preventable”. The level of homelessness we see in the UK is a choice. And as a country we could choose differently.